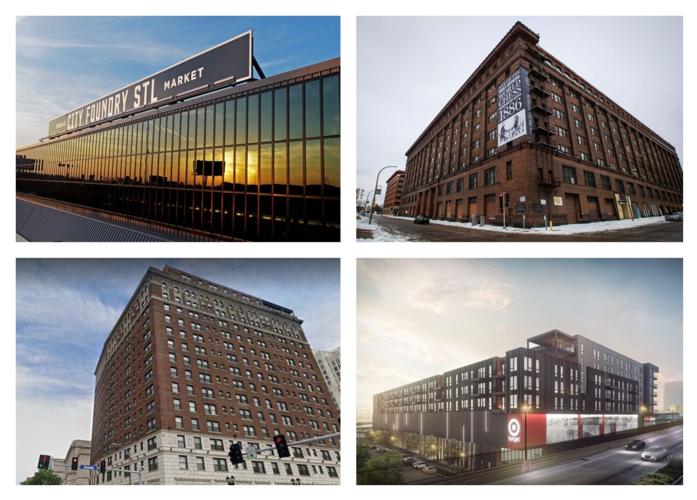

Four development projects receiving city incentives: City Foundry (top left), the Butler Brothers building (top right), Jesuit Hall (bottom left) and The Edwin (with a ground-level Target store). (Post-Dispatch file photos)

ST. LOUIS ŌĆö Less than three weeks after taking office, Tishaura O. Jones put developers on notice.

The cityŌĆÖs new mayor vetoed two developer tax breaks that she said were too generous. And then she held up final approval of incentive packages for two other projects that had long enjoyed almost unwavering political support ŌĆö the City Foundry food hall complex and another phase of development in the Cortex tech district.

The moves forced the developers back to the negotiating table and quickly demonstrated what anyone who had been listening to Jones campaign early this year should have expected: The old way of doing development in ├█č┐┤½├Į was over.

Directing this shift in the cityŌĆÖs approach is JonesŌĆÖ 28-year-old director of policy and development, Nahuel Fefer. Raised in the Boston area, Fefer came to ├█č┐┤½├Į to study at Washington University and later landed an economic policy job with Francis SlayŌĆÖs administration during the four-term mayorŌĆÖs final years in office. Fefer left to attend New York University School of Law and was admitted to the Missouri Bar this summer.

People are also reading…

Joining Fefer at the helm of the cityŌĆÖs economic development team is Neal Richardson. He was hired in June to replace the retiring Otis Williams, whose tenure at the ├█č┐┤½├Į Development Corporation (SLDC) stretched back more than 20 years, to the Clarence Harmon administration.

Richardson, 34, who earned an MBA at Webster University, grew up in north ├█č┐┤½├Į and has experience working with tax credits and other financing instruments at U.S. Bank. Fefer has focused his studies on tax policy and did a stint at legal advocacy group ArchCity Defenders shortly before he joined the Jones administration.

Nahuel Fefer (left) is the ├█č┐┤½├Į director of policy and development; Neal Richardson is the executive director of the ├█č┐┤½├Į Development Corporation.┬Ā

The two hold among the most powerful jobs in city government, roles where millions of dollars and generational investments into the urban fabric of the region are on the line. Now, theyŌĆÖre leading an experiment from a more progressive administration that believes development can still occur with less public subsidy.

ŌĆ£Developers should no longer assume abatements and incentives into their capital stack ŌĆö we need to have a conversation and they need to earn these incentives,ŌĆØ Fefer told the Post-Dispatch in a recent interview in which he likened the cityŌĆÖs role to that of any other investor or lender.

ŌĆ£This may be a novel concept for city government, but it is not a novel concept for the financial sector,ŌĆØ he said.

The point of the harder negotiating stance, Fefer and Richardson say, isnŌĆÖt just to protect tax dollars, but to promote more equitable development policies across the city, encouraging mixed-income communities and leveraging the economic strength of the central corridor to spur social change.

Privately, people in the development community worry that the new regime could choke off investment in a still-shrinking city that can ill-afford to discourage a limited pool of active developers free to chase higher returns elsewhere in the region or in other cities. The uncertainty over what City Hall will provide, what it expects in return and the amount of profit a developer can make before the city recaptures some of the public incentive, is making some hesitate to propose new projects.

Indeed, the number of major new projects proposed at the cityŌĆÖs economic development boards has slowed in recent months. At one of the most active boards, the Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority, the number of development agenda items through November this year was half of the roughly 80 through November 2020, even with pandemic uncertainty at its height. At least one big project ŌĆö the first apartments planned for the Cortex district ŌĆö appears to have stalled, with no movement on the proposal since the Jones administration restarted negotiations on incentives.

There are still developments, particularly in the relatively strong central corridor, already under construction. Yet whether momentum continues and new projects break ground, with or without city subsidies, remains to be seen.

ŌĆ£The core is as strong as ├█č┐┤½├Į has,ŌĆØ said one member of the development community. ŌĆ£But that doesnŌĆÖt mean itŌĆÖs Austin, Texas, either.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśHard to understandŌĆÖ

A new approach from a new administration is to be expected, those in development say. But even more so than the amount of incentive, itŌĆÖs uncertainty about what the administration expects from developers and is willing to offer in exchange that could be the biggest drag on new investment. Does the city want affordable housing incorporated into a project? How much? Are contributions to the school district required? How much profit can an investor make before the city tries to claw back any incentives?

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs hard to understand what their position is,ŌĆØ said one person who has been involved in the negotiations but who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of jeopardizing future deals with the city. ŌĆ£It was a constantly moving target.ŌĆØ

Fefer acknowledges developer uncertainty about the cityŌĆÖs future role in deals, saying during an SLDC board meeting in September that the city has ŌĆ£heard the development community loud and clearŌĆØ that they want ŌĆ£clear processes and policies.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I think itŌĆÖs undeniable to say the transition created a disruption,ŌĆØ he told the Post-Dispatch.

While developers and City Hall take a cooperative tone in public, behind the scenes, negotiations grew tense over the Butler Brothers and City Foundry projects. The new administration inherited those projects midstream, and Fefer said negotiations on future projects can start much earlier, hopefully leading to better outcomes for both the public and developers.

ŌĆ£I recognize that we have slowed down some deals and thatŌĆÖs unfortunate, and itŌĆÖs unfortunate we couldnŌĆÖt reach agreement more quickly,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£But I think moving forward what weŌĆÖre looking to do is build a process that actually allows us to make strong community benefit agreements and strong commitments on the part of developers in a more expeditious manner.ŌĆØ

Even so, Fefer and Richardson say developers should still expect to negotiate deals on an individual basis with the mayorŌĆÖs office and staff at SLDC. ThatŌĆÖs not a complete departure from past practice, but for the last 20 years, some degree of city support for anyone willing to invest in development here was all but a given. City Hall routinely granted tax breaks to developers with little to no controversy.

Though the city began dialing back incentives and taking a more analytical approach in recent years, the city stuck to negotiations over the amount of incentive, lending the process a bit more certainty.

Now, under the Jones administration, incentive negotiations encompass more than just the amount of tax breaks. Affordable housing, public school contributions and other public contributions are on the table.

ŌĆ£If they want public dollars, they need to be producing public goods,ŌĆØ Fefer said. ŌĆ£City residents have made it clear they take that very seriously.ŌĆØ

Fefer and Richardson said they are working to establish some guidelines. A new ŌĆ£economic justice action planŌĆØ under development that SLDC staff had hoped to release this month will include some of those criteria. It is now set for a March rollout, Richardson said.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs no cookie-cutter approach to this,ŌĆØ Richardson said. ŌĆ£We still have to be active partners. Just like every other investor, they have a set of criteria you must meet, and then you negotiate from there. We have to set the benchmark, this is what we expect.ŌĆØ

Mixed income

To Fefer and Richardson, incentives represent key leverage points to implement what they say is JonesŌĆÖ vision for equitable growth ŌĆö a vision they argue will ultimately help the economy and grow population by encouraging mixed-income communities and alleviating concentrated poverty.

Businesses refuse to locate in whole swaths of the region where incomes are too low, Richardson said. Employers complain they canŌĆÖt find workers; workers canŌĆÖt afford to live near where many service sector jobs are. Crime rises amid concentrated poverty, people flee and neighborhoods crumble.

Of the deals negotiated so far by the Jones administration, a theme has emerged: developers who want incentives are likely to be pushed to include a contribution to affordable housing.

ŌĆó The City Foundry deal required the developer to contribute $1.8 million to the cityŌĆÖs affordable housing trust fund, which helps finance affordable projects around the city.

ŌĆó The recently negotiated Butler Brothers project in Downtown West agreed, in exchange for 15 years of tax abatement, to limit a quarter of its planned 385 apartments to rents deemed affordable to people making up to 120% of the areaŌĆÖs median income.

ŌĆó The Jesuit Hall developer agreed to maintain 19 affordable housing units within certain north ├█č┐┤½├Į census tracts.

ŌĆó The recently announced $60 million, 200-unit apartment development anchored by Target in Midtown agreed to limit rents in 10% of its units to levels deemed affordable for those making below the median income in exchange for a break on construction material sales taxes. Hopefully, that will help ensure some of the people working at Target can live above it, too, Richardson said.

ŌĆ£If we are creating these mixed income projects, where we have low- to moderate-income families living in the same buildings and neighborhoods as higher-income folks, theyŌĆÖre going to have accessibility to amenities that may not be afforded to them if we continue on this trajectory of concentrated poverty and being separated and segregated,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs why we take it very seriously. Because we donŌĆÖt see it just as a (development) project. We see it as a mindset shift. We see it as a narrative shift in how our city moves forward.ŌĆØ

Alderman Jeffrey Boyd, who chairs the aldermanic Housing, Urban Development and Zoning Committee that sees many of these big projects, said the new administration ŌĆ£isnŌĆÖt giving away anything.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Talk about scrutinize ŌĆö they are on hyper-speed, which is a good thing,ŌĆØ Boyd said at a recent hearing on the Target project deal. ŌĆ£I canŌĆÖt imagine this was a walk in the park.ŌĆØ

Other incentive deals could include contributions to ├█č┐┤½├Į Public Schools, the entity most reliant on property tax revenue but which has little say in the awarding of tax incentives. The Armory project in Midtown, for instance, could be asked to make a contribution to the schools in exchange for its next phase of tax increment financing.

Deli Star, a food processing facility moving its facilities from outstate Illinois to Midtown with plans to grow to 475 jobs, agreed as part of its deal for 50% tax abatement to give ŌĆ£priority reviewŌĆØ to ├█č┐┤½├Į Public School graduates who apply for jobs. The company also will make a small, $2,500 donation to the city schools foundation, participate in SLPS career events and examine internship opportunities, according to a copy of the agreement.

Fefer emphasized tax abatement deals now include more stringent clawback clauses, triggered if a developer earns above a certain amount, particularly by selling a property. SLDC previously used clawbacks mostly to make sure developers spent as much as they promised, and last year, before Jones took office, it began crafting a new policy to recoup some incentives if developers flipped properties for big profits.

ŌĆ£If they ever end up making a killing, the city gets more of its money back,ŌĆØ Fefer said, adding that some developers have used their abatements to boost the sale price of their projects, ŌĆ£which just represents padding their bottom line with taxpayer dollars.ŌĆØ

The new clawback policy represents another point of contention: City Hall will be negotiating over how much developers can earn before clawbacks kick in. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs the million-dollar question,ŌĆØ Fefer said.

To enforce those clawback clauses, developers must also agree to submit detailed financial statements to the city. But that, Fefer and Richardson say, is no different than what their construction lenders would expect from them.

ŌĆ£We may be an exception, but as we think about the overall financial industry as we underwrite deals, we want to look at it in the same way,ŌĆØ Richardson said. ŌĆ£We are willing and able and active partners in finding how we can help close those financing gaps. We want to be the gap filler. We donŌĆÖt want to be the first ones into the transaction.ŌĆØ