ST. CHARLES COUNTY — Bob Rhodes enjoyed his time working at the Weldon Spring nuclear site.

It was the early 1980s. The former Mallinckrodt ordnance center, involved in uranium production during the early nuclear age, had been shut down for years but not yet transferred to the Department of Energy for cleanup.

Rhodes was at the site with three other union electricians, all members of the , working for a subcontractor. They were stringing electrical conduit on fences around the facility and installing monitors to test the air for radiation. They went in and out of buildings, around the perimeter and on a boat to cross canals around the quarry.

“Construction sites are generally noisy,” he says. “It was a nice, quiet job.”

It was also a job that Rhodes and his fellow workers did without proper protection, unaware of the potential health ramifications. Rhodes didn’t think much about it at the time.

People are also reading…

“We weren’t wearing suits or masks or anything,” he says. “We didn’t have a clue.”

So it was for a generation of American workers at nuclear sites from the 1940s to the 1980s. They helped the country build the atomic bomb and stock its nuclear arsenal, only to pay the price later with various health issues.

Denise Brock’s father, Christopher Davis, died too young because of his work around uranium. He was the reason Brock worked with other activists, including longtime environmentalist Kay Drey, to push for Congressional approval of the . The law, passed in 2000, has paid out more than $22 billion in medical claims.

Last year, Rhodes filed a claim. He heard about the program because of a new wave of publicity.

In 2022, Brock pushed for a tribute to workers to have a special location in the new Weldon Spring Interpretive Center, a museum about the ��ѿ��ý area’s connection to the nuclear age. She won the battle. Around that time, a new activist group called was pushing for a law to compensate homeowners around the Coldwater Creek area in north ��ѿ��ý County, as well as Weldon Spring and other locations, for radiation pollution in their communities.

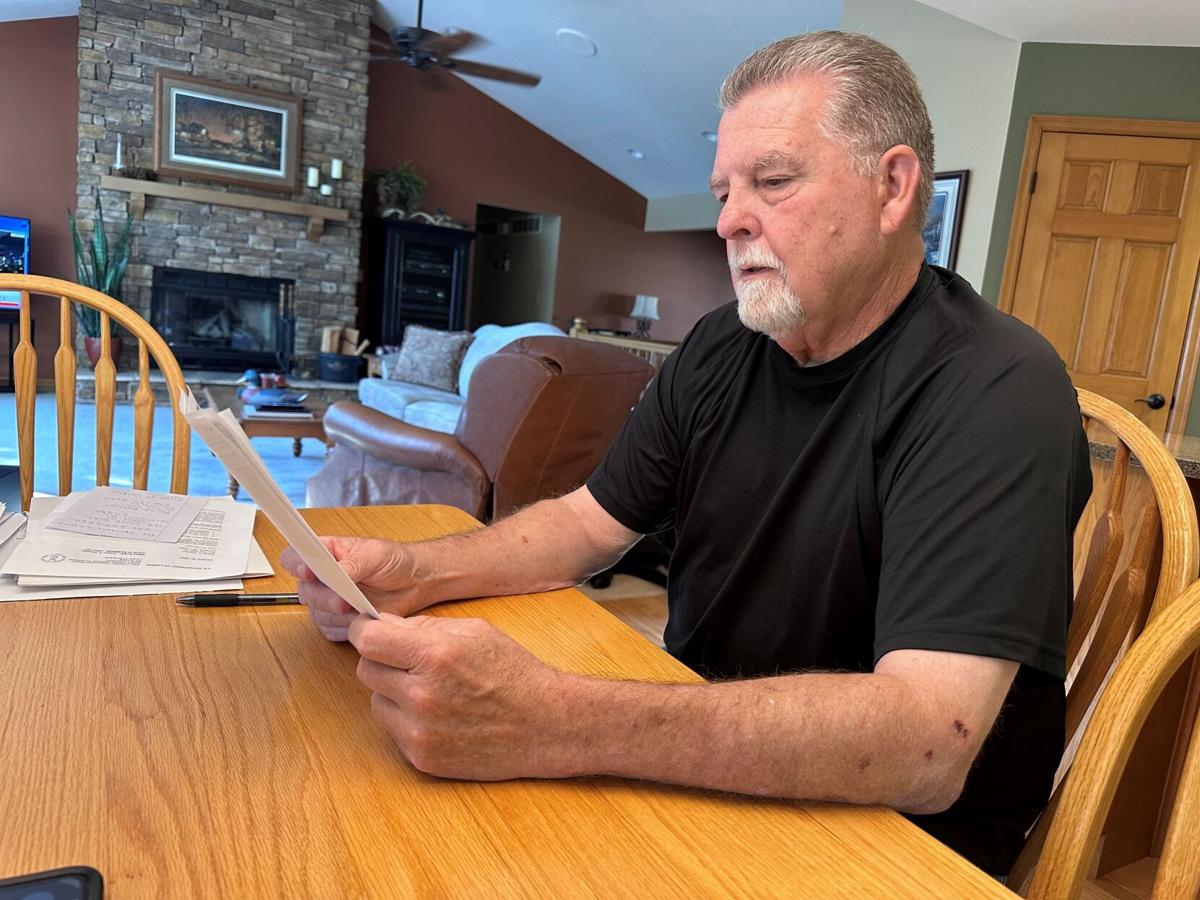

That legislation has been stalled. But in the meantime, Rhodes, who has neuropathy and tumors, filed a claim under the energy employees’ compensation program. In May, his claim was denied.

“They couldn’t find my work history,” Rhodes says. “I went through all the paperwork, all the physicals. I did everything they asked of me. They kept denying my claim.”

Rhodes wasn’t alone. Dozens of workers, perhaps hundreds, have had their claims denied because the federal government couldn’t find records that tied them directly to a uranium site. Brock, who helps people file claims for the program, decided to figure out what was happening.

It turns out that somewhere in a government office, in a closet or basement, a couple of buried boxes contained records of all the contractors and subcontractors who worked at uranium sites but didn’t get a paycheck directly from Mallinckrodt. Brock alerted the Department of Labor and Department of Energy, which are both involved in the compensation program.

Last month, at a Department of Energy fair in St. Charles County, Brock : the records had been found, and workers like Rhodes would have their claims re-filed automatically. The records affect employees who worked for at least 25 different subcontractors, Brock says.

“So many people were filing claims and they knew they worked out there,” Brock says. “They weren’t lying ... The ball got dropped somewhere along the line and there wasn’t enough outreach that was done. All of this discussion about Coldwater Creek that’s been in the news started the ball rolling again, and people started coming forward, filing claims.”

There’s no guarantee that Rhodes will get compensated. But at least now, the government won’t ignore him because it can’t connect him to the site where he worked more than four decades ago.

He and his wife, Jan, now live in Defiance, not far from that former nuclear site. Rhodes is still healthy enough to mow his lawn and sit and have a beer while he admires his work. He spends time at a farm in nearby Montgomery County. Just like the time he strung conduit to radiation monitors, he enjoys the peace and quiet — though he still misses the work.

Meanwhile, as he awaits word on his claim, he appreciates that Brock, ever the activist, is still going to bat for the workers at Weldon Spring.

“She can move a boulder if she puts her mind to it,” Rhodes says. “It looks like this is going to help a lot of people.”