And so I act the part of the dutiful daughter. I bring him his tea in the morning and rub his feet at night. I pretend not to hear him joining in the laughter when the men at the tea shop joke about the difference between fathering a son and marrying off a daughter.

A son will always be a son, they say. But a girl is like a goat. Good as long as she gives you milk and butter. But not worth crying over when itâs time to make stew ...

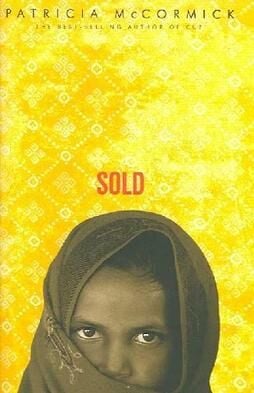

That unsettling passage, early in the award-winning novel â,â foreshadows the nightmarish ordeal ahead for Lakshmi, its narrator and protagonist. The 13-year-old Nepalese girl is subsequently shipped off to India and sold into sexual slavery by her stepfather.

American journalist Patricia McCormickâs book has been lauded as a moving, accessible and well-researched look inside third-world sex trafficking for audiences that might otherwise remain ignorant about that hellscape.

People are also reading…

But for students of the Wentzville School District, that window of knowledge has once again been slammed shut. Based on a complaint by exactly one parent, followed by a one-vote margin on the school board, the district last week officially banned the book from its school libraries.

Itâs not the first book the busy censors of the district have banished. They made humiliating national news a few years ago by briefly yanking the Toni Morrison literary classic âThe Bluest Eyeâ from shelves. There have been others.

But this removal is notable in that the book, though fictional, tells the story of a real-life tragedy in the world today, in straightforward prose without vulgarity or gratuitousness.

Yes, the subject matter is disturbing, but sex trafficking is a real phenomenon that some of todayâs students will someday have the power to confront as future leaders on the national and world stages. Yet even a recommendation by the districtâs own review committee that the book remain on high school library shelves and only be shielded from lower grades was rejected by the board.

Itâs a perfect example of how book-banning policies â even those originally prompted by the relatively rare library fumble (remember the firestorm at the St. Charles City-County Library for stocking one copy of the title âBang Like a Pornstarâ?) â will inevitably invite censorship against more serious and worthy material.

Wentzvilleâs hair-trigger book-banning process in particular is an open invitation to any random culture-warrior to muzzle discussion of serious topics. All it takes to require a review of a book is a complaint from one parent who doesnât want anyone to have such discussions. That single complaint, regardless of its reasoning, requires a review of the book by a committee of teachers, parents and others, which makes a recommendation to the school board.

The board is free to ignore that recommendation, which it did in this case. By a 3-4 vote, the board bypassed the judgment of parents and others on the committee, who reported that the book is âa beautiful story to show the main characterâs resilience to get back to her familyâ and that it avoids obscenity or raunchiness.

The board sided instead with the original parent-complainant â who, as the Post-Dispatchâs Monica Obradovic reported this week, blithely refers on social media to books she dislikes as âdisgusting smut.â

Itâs telling how often the books that end up being banned these days, at Wentzville and elsewhere, focus on issues related to racial or cultural minorities. The empathetic protagonist in âSold,â like the empathetic protagonist in âThe Bluest Eye,â is a girl of color. Go figure.

Censorship trends reflect political trends. When liberal politics was ascendant in earlier eras, âThe Adventures of Huckleberry Finnâ was a frequent target of censors who myopically focused on its offensive use of the n-word, a complaint that missed its broader message of racial tolerance.

Today, racial tolerance itself is targeted by censors appeasing right-wing ideologues who disparage almost any discussion of race at all as âwokeâ or âDEI.â That definitely serves a certain kind of agenda out there â but not any agenda that involves a well-rounded education for kids about the world they will inherit.

A recurring theme in âSoldâ is about the voicelessness of sex trafficking victims. Giving voice to such victims is a noble function of serious literature like this. Muzzling those voices at the behest of any culture-war crank who can fill out a form shouldnât be the function of a school board.